I’m a researcher at the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity where I direct the Daylight Lab. I’m interested in structural risks to the global internet.

Today, I’m writing about internets, and why a governable one would be good—if we had a government we could trust to the job.

This post is the first part of a series.

Background: This Internet, on the Ground

→ Part 1. Governable internets

Part 2. How governance could be

Part 3. What are DAOs?

Part 4. An internet of DAOs

Part 5. Identity bureaus

Part 6. But can it govern?

Part 7. Pockets of liberation

Governance

Like the word “information,” “governance” can slip a lot of details under the rug.1 OED unhelpfully defines governance as “the office, function, or power of governing; authority or permission to govern.” So what does it mean to govern?

When we say someone governs—for example, “the UC Regents govern the University of California system”—we mean that the they make the rules. That their rules are the real rules and, if we ignore or flout them, followers of the real rules will use that ruleset to seek sanctions against us (firing us, or whatever other mechanism the rules provide). Their success proves the legitimacy of the ruleset, further entrenching it.

In other words, governance is a social contract, like money. (Indeed, money is a sort of governance). It’s a contract that can be bound, or made more binding, by legitimated violence. This is how Weber defines a state.

It’s also a contract that can be broken.

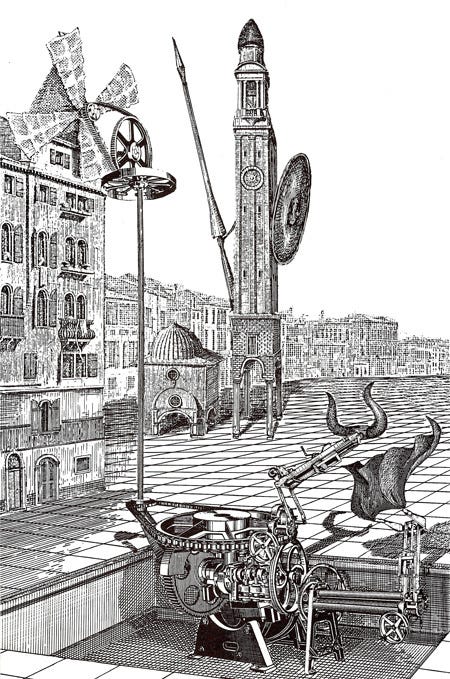

I hate to even show you this picture, but it’s meant to remind us that the internet must be governable. An ungovernable internet can and will subvert the government that hosts it.2 A primary job of any government is to govern its technologies, including its internets.

Governing an internet

What does it mean to govern an internet? Even for those steeped in “internet governance” discourse,3 it’s hard to imagine what a governable internet might look like.

A material thing

Part of the difficulty: we’re trained to imagine an internet that’s ethereal, fleeting, immaterial. Ungovernable, by virtue of being apart from the here and now.

As we know, this internet is anything but. It unfolds across diverse material forms: light pulses under the sea, radio waves in the air, electricity through coaxial cable (yes, still!). Thinking about these material forms as one coherent thing is abstract, but its abstractness does not make this internet immaterial. This internet is only material.

What should governance be?

So what does it mean to govern this thing that is the internet? Narrowly, it means to influence the material conditions of the internet, directly or indirectly. Simple enough. But what should it mean to govern an internet? What kinds of “material conditions” should governance influence? Who decides what material conditions should governance influence? In other words, what would it look like to govern an internet well?

In the broadest sense, a governable internet must have two mechanisms:

A mechanism to adjudicate disputes over computer networks—disputes between citizens, and between citizens and the government.

A mechanism by which the network can be shaped by popular will.

I’ve left much to the imagination in the particulars here. On what scale will this “popular will” be enacted? Whose will, exactly? Who decides whose will?

And what important questions these are.

How governance is

In practice, people (perhaps you!) have been allergic to the concept of government intervention in the internet. Indeed, in the hearts and minds of many civil libertarian groups, John Perry Barlow’s independent cyberspace lives on. “The internet should be ungovernable!” At least to a degree. This is the thesis at the heart of the pro-encryption absolutist side of the end-to-end encryption debate in the U.S. and beyond.

The allergy to governments meddling in the internet, of which pro-encryption extremism is merely a symptom, is well-founded. It’s motivated by nation-states’ historical relationships to this internet.

To put a fine point on it: this allergy to internet governance has two causes: first, governments that disrespect civil liberties; and second, a global network that is itself resistant to any reasonable notion of legitimate governance. There is, in other words, both an institutions problem and an internet design problem. We’ll need to address both.

An institutions problem

Historically, internet governance has given civil liberties short shrift in practice: warentless wiretapping a la the Snowden revelations, and holding property without due process, a la Operation in our Sites (Kopel, 2013).

And that’s just to pick from the U.S. context. Globally, the internet faces traffic tampering, shutdowns, and more at the hands of states. Governance over the internet, as it’s been practiced, has been ad hoc and power-based. It has functioned without sufficient popular oversight, popular input. It represents a failure of our institutions to act in a meaningfully democratic way.

But the notion that governments should never interfere in the internet—that the internet is a realm where governments should always have some prespecified limit to their reach or impact—is, I believe, reactive to this internet’s particular historical conditions.

Good institutions are possible

The idea that no government could exist—no popular assembly, no type of government at all—whose legitimacy by virtue of its popular consent could in turn legitimate its control over some internet (not necessarily this one!): that’s a stronger claim than I’d reckon anyone can make.

The debate so far has been about getting this government to stay out of this internet. What we need a government we can trust to govern some internet. It is possible (indeed desirable!) to create a government that acts on and via any internet, as its citizenry deems fit.

An internet design problem

But good government alone will not a happy internet make.

This internet does not provide adequate affordances for governance. It does not provide adequate structures for adjudicating disputes between its users, or between users and the government. Nor does it have meaningful popular governance over its global “control points.”

No mechanism for adjudicating disputes

I’ve covered Operation in our Sites in some depth on this blog, but a question I haven’t answered is: why does the U.S. focus on domains? Of all possible tactics, why this one?

The answer is that it’s the simplest thing to do. Intellectual property law is the path of least resistance for the U.S. federal government. The path of least resistance in applying that law is civil forfeiture on intermediaries—the institutions, like domain registrars, that stand between the offender and their performance of the crime (Kesari et al., 2017). Since these intermediaries are the things that can be governed, they are the things that get governed. There is no other lever to pull.4

No mechanism for popular governance

Nor does this internet provide any structure for popular governance. Existent private companies are regulate-able only indirectly, through lawmaking. Public and open bodies, like ARIN and the IETF, while nominally open, are not meaningfully civic, as Cath (2021) demonstrates in her work with the IETF.5 Aside from any principles-based complaint about this internet’s governance structure, here’s a purely descriptive one: this governance model doesn’t work. Specifically, it doesn’t respond to the needs of people on the ground.

A better future is possible

Neither this internet nor these institutions are fit for the job of rigorous and democratic technical governance.

Our job is to imagine alternatives.

In the next few posts, I’ll work through just this. What governance institutions could look like, what kind of internet could accommodate those institutions. Some very political posts, some very technical ones. Then, I’ll fuse the two. I’ll argue that trust, mediated by systems of identity, can produce flexible and scaleable systems of popular governance.

The point I’ll try to convince you of is this: a properly designed internet can not just be governable, but can govern. A better internet can mediate, aid, structure, and undergird civic better institutions. It can fuse with them so thoroughly that it becomes difficult to tell where the government ends and the technology begins.

Next post → How governance could be

It’s what Geoffrey Nunberg would have called a “fruitcake word:” it gets passed around a lot, but few unpack it to see what's inside.

That’s not to say we need a surveilled internet, or a censored internet, or any other kind of internet ipso facto. It’s to say that an internet with no governance—or rather ad-hoc and power-based governance (in this internet’s case, one motivated by corporate profit alone)—is a dangerous thing. The forces that allowed this internet to shape MAGA, QAnon, and its exgeneses into a would-be revolutionary guard are a testament to the dangerousness of an internet on which popular governance is structurally impossible.

“Internet governance.” I don't love this term. It slices off the notion of governing the internet from the notion of using the internet to govern. No such slicing can occur: the internet is both reflects and shapes politics, domestically and globally (Douzet, 2014). It also overfits to this internet, as opposed to any other internet we might invent. But it's a term, and we must address it.

Following Hoffmann (2017), it’s best to take a capricious definition: internet governance is a “continuous heterogeneous process of ordering” the Internet, making room for both formal rule-making and emergent practices of users, providers and other stakeholders.” As van Eeten and Mueller (2012) articulate, formal governance bodies are only one of many institutions that structure this internet. Security incident response, content filtering, IXP interconnection, and other practices all shape this internet as we experience it.

This governance, this ordering, is intermediated by political action, some of which matters globally, much of which steps on civil liberties, and little of which receives due popular oversight.

The E.U.’s Digital Services Act promises to crank this dynamic with intermediaries up to eleven. The Washington Post, via Platformer:

The version approved Thursday would force companies to remove content that is considered illegal in the country where it is viewed, which could be Holocaust denials in Germany or racist postings in France. And it would significantly shape how companies interact with users, allowing Europeans to opt out of targeted advertising more easily and prohibiting companies from targeting advertisements at children.

Control over intermediaries is a poor substitute for direct governance over the network and its rules. But this internet's design was, in many ways, anti-governmental; it made no room for a government, was meant to make no room for one. (Merrill, 2021).

The IETF in particular is the target of nation-state capture and manipulation in practice, as has been well-documented in the case of China and Huawei's NewIP proposal to that body.

Just came across you purely because I liked the name else.how among the options for staking Juno.

Liked this article, what you're writing about and your overall writing and presentation style. Glad I found it.