Why dream?

This world To what may I liken it? To autumn fields lit dimly in the dusk by lightning flashes

—Minamoto-no-Shitago (911-93 AD). Source: Yoel Hoffman, Japanese Death Poems.

I write down all my dreams, and I dream vividly.

Why do we dream? There is no widely accepted explanation. Ancient Egyptians and Greeks believed dreams were visitations from the gods. Jung believed dreams were projections of the unconscious—projections that sought to compensate for the conscious mind’s distortions. Famously, Jung did not disparage the ancient understanding of dreams as divine visitations. He believed gods themselves to be archetypal, projections of a shared unconscious. (And he believed those archetypes were still with us—that “the gods have become our diseases”).

Today, computation is de jour. Computational explanations for dreaming have dominated neuroscience since the 1970s.

One such explanation is the overfitting hypothesis. Framing people as learning agents in interactive environments, it postulates that people “overfit:” that is, learn strategies overly specific to their past experiences, but not general enough to be useful in analogous but novel ones. To compensate, dreams provide simulated environments with noise injected, which makes our learning more robust.

Another explanation comes from experiments in reinforcement learning. Imagine a task in which a single wrong move spells disaster. Diffusing a bomb, for example. We can’t ask the agent to practice a thousand times; we can’t afford to have our robot explode 999 times. What can we do? One suggestion, from a team at Google DeepMind, is to give machine learning agents an imagination—to allow them to learn in a safe, if hallucinated, environment. The more they interact with the real environment, the more accurate their imagined environment will be, and the more useful the imagined activity will be in teaching them to perform the real task. Dreams, perhaps, are a sort of imagination-augmented learning.

Jung took great pains to make his theory square with earlier ones, however ancient. How do these new, computational theories square with the comparatively modern account Jung gave?

Both accounts frame dreaming as adaptive. Dreams are instructive, meant to help the individual develop. And both accounts frame dreams as compensatory—dreams compensate for the shortcomings of conscious experience.

But the accounts differ in important ways. In Jung’s thought, and in the beliefs of ancient people, dreams require conscious interpretation if we are to fully appreciate the benefits. Computational accounts would have us treat dreams as maintenance processes, the experience of which we are free to forget about. (Missing from these computational accounts is any explanation of why maintaining a conscious experience of our dreams after we wake, however partial, would be adaptive).

This difference points to a greater shortcoming of computational accounts, one that plagues the modern study of AI to this day: they undervalue the role of reflective consciousness. The ability to understand oneself as a reasoning agent is fundamental to our experience.1 Any computational account of the mind that doesn’t grapple with this capacity is bound to miss something important.

Computational work may help us slouch toward a better understanding of what dreaming is and why it emerged in animals, so long as it doesn’t monopolize the conversation.

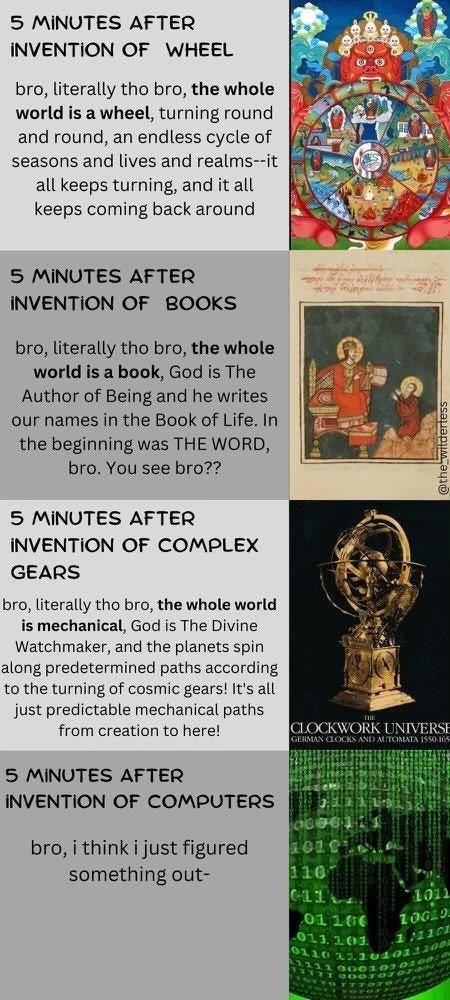

It makes sense to me that, in the absence of any contradicting narrative, ancient people assumed dreams were visitations from the divine realm. It’s telling that metaphors rooted in technology have gradually replaced that account. Machines are the new divine.

As I’ve argued before, our ideas about the mind have always moved relative to the capacities of contemporary technology. What’s unique to this moment is that machines, particularly AI, are framed as both mirrors of ourselves and something potentially more powerful. They are modeled after us, yet somehow capable of transcending our limitations. They are the image of Adam’s rib in reverse: we summon gods from our own image.

Setting aside the merits or detriments of any computational claim about mind or consciousness: do we want to be computational? In an ongoing spiritual crisis, of which skyrocketing mental health symptoms among adolescents are but one symptom, what makes us feel more at home in ourselves: that we are reinforcement learners, searching for a policy that maximizes reward? Or that we are animals, visited in dreams by the mysterious? Which of these stories lets us live the lives we want to live?

Personally, dreams are the only narrative form I trust. They're the only stories I experience that don't have someone else's motives behind them. Any story someone else tells me wants my time, money, to see things someone else’s way. Dreams happen for me and by me. If they want anything, it's for me to survive.

Thanks to Luke Loseth for the conversation and meme.

Large language models like GPT have no reflective consciousness. That’s why saying GPT is “slightly conscious” is like saying a field of wheat is “slightly pasta.”