This post is part of a series.

Background: This Internet, on the Ground

Part 1. Governable internets

Part 2. How governance could be

Part 3. What are DAOs?

Part 4. An internet of DAOs

→ Part 5. Identity bureaus

Part 6. But can it govern?

Part 7. Pockets of liberation

Interest in web3 (or ‘crypto’) is borne of widespread dissatisfaction with dominant institutions. Direct democracy in the mold of Murray Bookchink’s popular assemblies could replace these institutions with forms beyond kleptocratic neoliberalism. But how would such a system begin?

This week, I’ll describe my proposal: identity bureaus, grassroots organizations that connect web3 ideas to a coherent political ideology. I argue that identity bureaus, if constructed carefully, could facilitate a transition to grassroots, direct democracy in the contemporary West.

Last time, I sketched a logic of global data trade that emerges from the sovereignty of self-governing autonomous systems (AS DAOs). And, throughout this series, I promised popular governance—or at least that popular governance should be possible in such a system. (I’ve referenced Bookchin’s popular assemblies as a model—a high bar for direct democracy!).

To make good on this promise of popular governance, I’ll have to answer two questions that my technical sketch left underspecified:

Who’s included? Will these AS DAOs be popular democracies, ruled by the many, or technocratic dictatorships, ruled by the few who possess sufficient technical knowledge?

Do we trust the elections on these AS DAOs? Manipulations of democratic systems plague our political moment in the U.S. Are these elections trustworthy?

These are political questions. Institutions will determine their answers.

This post introduces an institution—the identity bureau—that I argue can make good on the promise of direct democracy in self-governing ASs. In fact, these institutions reframe our discussion of internet governance away from designing internets amenable to governance and toward designing internets that can act as governments—sovereign actors in a system of global data trade.

The ballot-stuffing question

Let’s start with the ballot-stuffing question.

(Given that we’ve been talking about grand ideas like global data trade and direct democracy, you may be surprised that ballot-stuffing is my starting point. It’s hardly the thorniest issue I’ve touched on. Yet getting our grips on this issue helps us motivate identity bureaus directly and simply.).

In our AS DAO system, what prevents someone from manufacturing wallets and gobbling up address tokens—buying them off of people or stealing them—to consolidate their voting share and manipulate the DAO’s governance? If identities can be made freely, richer parties will accumulate an advantage gobbling up governance tokens.

In technical parlance, this is a sibyl attack. In a sibyl attack, an attacker creates a large number of identities and uses them to gain disproportionate influence. (Sibyl attacks correspond to the “dead people are voting” threat model in electoral democracies.)

From the perspective of our ASs, as in electoral democracies, the question of how to prevent sibyl attacks is best framed like this: what is that process that relates ownership over identities to natural-born persons?

Here enters the identity bureau.

The identity bureau

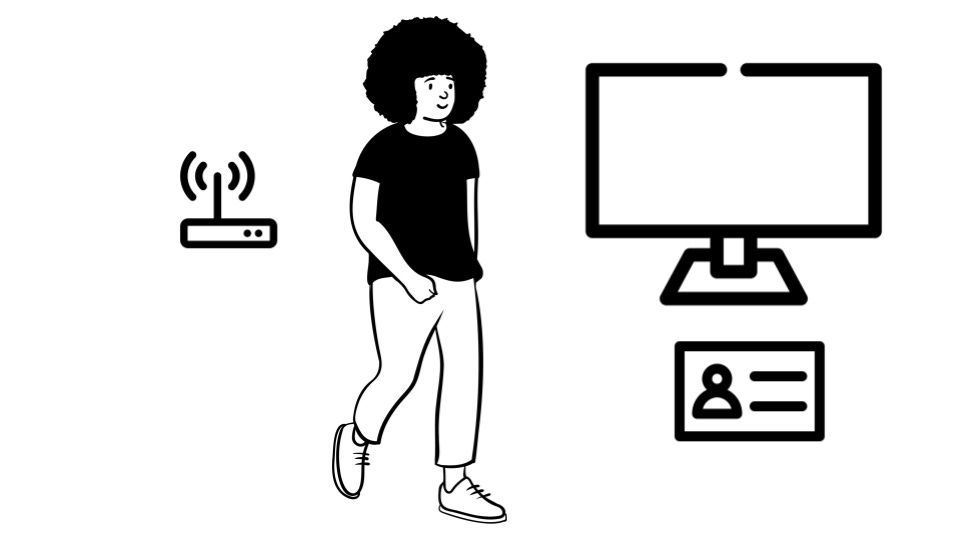

Let’s start from the perspective of a person. We’ll call that person “you.”

You have a router/modem. You want to connect to this new local internet you’ve heard about.

So, you go down and present yourself in person at a community hub. The role of this institution, of the people at this community hub, is to verify grant you a cryptographic identity, verifying that this identity has a one-to-one relationship with natural-born persons.1 Think of it as a community-run DMV.

The rep at this community hub will hand you a physical ID card. Like many identity cards in Europe and beyond, this card contains your cryptographic keypair, which can be used to sign transactions.2

You return home with your ID card.

You plug the ID card into your router/modem and enter a PIN. The router/modem flashes green and you remove your ID card.3

Your router is connected to the internet! You put your ID back in your handbag with all your other forms of identification.

Now you’re online! You’re connected to the local internet. You can control your WiFi network as you always have, give out your WiFi password as you always have.

When it comes time to vote on proposals at the AS DAO level, you can stick that identification card into your computer to cast your vote. (The community hub can give you the hardware required to do all of this.)

The AS DAO is subject to the governance proposals of its token holders. But now, the AS DAO can rest assured that the wallets voting have a one-to-one relationship to the sort of natural-born persons that they’d want to participate in a fair governance system (as opposed to corporations, fake identities, and so on).

Equity

As framed, identity bureaus are a straightforward solution to the ballot-stuffing issue.: they assure a one-to-one relationship between “valid” wallets (those the AS accepts) and natural-born persons.

But, to this blog’s critical readers, identity bureaus will raise more questions than they answer. If you’ve read ethnographic work on existing self-sovereign identity projects (e.g., Cheesman, 2020), your alarm bells should be going off. How do these identities embed and enforce logics of power and oppression?

After all, not everyone will be interested in joining a new internet. Who has the time for such a thing, let alone the expertise? That kind of governance is privileged and technocratic from the get-go.4 If only the community’s most technically adventurous join the system, we’ll have a technocratic imbalance in representation.

Clearly, the identity bureau will need to incentivize broad participation if it is to become a true popular assembly.5

Imagine for a moment that everyone in a relevant community—say, everyone in your neighborhood—already has an identity card, even if they haven’t yet used it to connect to the internet. Even if these folks aren’t interested in the internet nor in its governance, we can still grant them some address tokens to use, should they ever change their mind. They have the theoretical capacity to vote and make governance decisions.

Yet this “solution” presents a secondary problem: how do we get people to sign up, even if they aren’t interested in this whole internet thing? Mobilizing an active citizenry is central to the democratic project. How do we mobilize today’s neoliberal subjects into a politically active polis?

A simple answer: we give them free crypto.

Local currencies

The bureau can pay them to sign up. Those who sign up for the local identity system can receive the locally issued currency, which they can exchange for other tokens, or for goods and services.

If this sounds far-fetched, consider: many DAOs begin with an “airdrop”: an initial allocation of tokens to a select group of individuals. How these individuals are selected is the subject of much contention. At worst, these airdrops are a rich-get-richer scheme in which early adopters accumulate more goods. At best, they reward those with the technical privilege to use these new technologies.

In a popular assembly, however, all local currency tokens will be airdropped to local community members (ideally progressively, accounting for reparations for historical harms, state violence). This local currency can and should be exchangeable for nation-state fiat currencies, or any other token. There need not be limitations; its value must derive from its exchangeability.6

Actual democracy in actual communities

Were I to stop my description now, this system would likely converge on technocracy. A technical elite, provisioning the system, shape it to their own goals, with the many—the polis—only nominally participating. This likely outcome drives the “yuck factor” behind Sam Altman’s project to scan eyeballs in exchange for airdrops. Such a system would produce not even consultative (let alone direct) democracy.

Real democracy happens in the streets. We cannot lose sight of this fact. Yet an effective strategy for producing a meaningfully democratic society has eluded Western thinkers. Theoreticians have proposed electing officials at municipal levels, yet those efforts have amounted to little. In the context of the liberal West, theories of direct democracy lack a clear revolutionary narrative. How does it all begin?

My contribution to theories of revolutionary grassroots direct democracy is this: identity bureaus, funded with airdrops of local currency, are a starting point to building popular assemblies in actually-existing municipalities in the West.

Interest in web3 is borne of revulsion

Interest in web3 (or ‘crypto’) is borne of widespread dissatisfaction, even revulsion, with dominant institutions. It represents fear of a future in which these institutions continue to govern. Fear, and a wish. Could this technology lead us somewhere, anywhere else?

In connecting web3 with a coherent theory of a new world, identity bureaus can motivate and facilitate direct democratic organizers to build grassroots democracy—the types of robust institutions that could facilitate non-violent revolutionary change, absorbing the functions of governance until the vestigial state, no longer useful, wilts away.

For the next few posts, I’m going to show how popular assemblies built from identity bureaus and AS DAOs could produce the functions of the state that democratic thinkers care about: legislatures, courts, frameworks of property rights, management of the commons, and so on.

I’ll describe how DAOs in particular allow these assemblies to form affinity groups on flexible geographies of partially overlapping jurisdictions, enabling true freedom of association—something long dear to left thinkers. While DAOs will not promise the end of geography, ‘blocs’ of popular assemblies could produce complex structures within which identity, data flows, and likely physical movement will be fluid.

Yet this is no utopian project. Remember Schelling's model of segregation: even mild inclinations toward one’s “in-group” can lead to a highly segregated society over time. Between blocs, friction could increase to the same or even greater level than with current nation-state systems. Grappling with this fact will be a key theoretical and practical concern.

I’ll chew through all of this in the coming weeks.

Until then.

How do identity bureaus relate the person in front of them to a natural-born person? Biometrics present an easy, if fraught, solution. More on this topic another time.

For those of you who study digital identity specifically, think of this ID card in analogy to the Estonian identity system.

Under the hood, your keycard helps the router sign a “connect to the internet” transaction. It sends the signed transaction to the AS, which grants it an address token to use.

Tech delegation. Even those who do want to join may not be interested in, or qualified to, make governance decisions. How do we deal with that problem?

Recall also that DAOs allow delegation, whereby a token holder can allow a second party to vote on their behalf. The token holder may still vote, overriding the vote of the person to whom they delegated. But the process of delegation allows some degree of representative democracy in a system where decision-making is bound to be highly technical.

And what about privacy and data rights? There’s a tension between privacy and security in identity systems: privacy is good, but so is making sure that identities are authentic. Managing this tradeoff is the heart of contemporary securitization. How to manage it well is a question for another time.

Note also: with governance over this currency system, popular assemblies can levy taxes, maintain a treasury of these tokens, use that treasury to fund all manner of social services. More on that next time.